I’ve recently composed a new piece for The Hermes Experiment for them to record as part of my upcoming portrait CD to be released on Delphian Records.

I had a really great workshop of the piece with The Hermes Experiment on 16 June and I wanted to document the key points that I learned from this session. I came away from it feeling broadly very pleased with what I have written – it’s always nerve-wracking hearing something you’ve composed being played for the first time, and on that front I felt really relieved and happy in terms of how the piece flows and is coming together. But equally, following the session my head was filled with ideas for tweaks and revisions that I will make leading up to the recording in September.

A bit of background about the piece

The instrumentation for the piece is soprano, Bb clarinet (doubling on bass clarinet), harp and double bass, and the overall anticipated duration will be c. 15 minutes.

The piece is a song cycle titled The Indifferent and consists of 5 movements/songs. The text for this cycle is by Australian poet Judith Bishop. It’s a bespoke re-working of her poem (of the same title) that she created especially for me to use in this project which transforms the original poem from one continuous unit into 5 smaller texts (in Event Poems, Salt Publishing, 2007).

Writing for soprano

The two key findings from the workshop were that I have tended to concentrate a little too much for too long in the lower region of the soprano’s (Héloïse Werner’s) register, and also, a number of the phrases need either to be contracted or perhaps divided into two phrases to accommodate breathing. Indeed, what I appreciate much more acutely now is how closely these two points are interconnected. Singers require more air to produce notes lower in their register, which is Héloïse’s case is anything below the G4 or A4. So the result of writing melodic phrases that hover just below this region (as in the first movement) is that phrases need to be shrunk down a little in terms of duration. An example of this is in song 1, bars 18-21. Note that the metronome marking at this point is crotchet = 72. In this case, reducing the final dotted minim to a crotchet will bring the phrase into a more comfortable length.

Another angle that we considered concerns the context in which the soprano’s lines sit. For instance, in the first song the clarinet plays a lot of imitative melody in the same register as the soprano. This of course has the effect of masking the soprano’s part. I quite like the dialogic nature of this, but I can see ways to ameliorate the problem of masking:

We agreed that this could be addressed by reducing the extent to which the two parts play simultaneously. So in bar 11, going into bar 12, if the clarinet’s minim is minim reduced to a quaver, this creates more “room” for the voice to project through and be heard. Similarly. in bar 15, I plan to reduce the sustained G natural to come off after the first quaver of beat 3.

Another, more radical, revision might would be to employ bass clarinet in this song, building lines that reinforce resonance projecting from the double bass and harp (for example, at bar 27-28, the bass clarinet could perhaps play a low Db). This could sound really beautiful (but at the cost of eliminating some of the imitative writing) so I’m currently weighing up these options in the course of preparing the final version.

We spent some time deliberating over whether I would be best to shift some of my lower-pitched phrases up to a higher register. In some cases this is what I will do (eg. in bar 42 of the second song, an option I’m exploring is perhaps to flip what was a low D up an octave, or do something else to avoid returning to the low D).

Reflecting on this, even though I know I’d absorbed myself a lot in listening to recordings made by The Hermes Experiment and Héloïse Werner’s own solo album, I suspect that I have been influenced by the range and limits of of my own voice (which is basically an alto). I’m so glad that I’ve had the opportunity prior to recording to consider this dimension further and to make changes where I feel they are necessary.

I should say, there are places where I feel I have successfully harnessed Héloïse’s strongest (upper) register, such as in the final song. Example 5 below was a brilliant moment for me where I could really hear her voice “take flight”. And indeed, we noted after running through all five songs, that there is a gradual ascent through the soprano’s register across the work as a whole, which I wasn’t entirely conscious of when composing, but I think works very well (an over-arching sense of building up to a peak). Having said this, even here I discovered that I’ll need to shave a crotchet off the final tied E:

While chatting with Héloïse about this passage, I brought up a question which is constantly on my mind when composing for voice, namely, how much should I aim to embed notes of the singer’s part in the other instrumental lines? In the context of writing for choir, particularly community choir which I was doing recently, I know how crucial it is to embed “clues” to assist singers to pitch entries of new phrases etc. But writing for a professional virtuoso soloist in the case of Héloïse Werner is a different situation, and she indicated that while it’s nice to be provided with embedded cues and supporting notes, she can “pitch off anything”. So this is a key finding that I will take away and apply to any edits that I make to this piece and to my soloist vocal writing going forward.

So for example, at figure G in song 4, I plan to shift this phrase up in register without necessarily planting anchor notes into the surrounding texture.

To use the bass clarinet, or not to use the bass clarinet, that is the question…

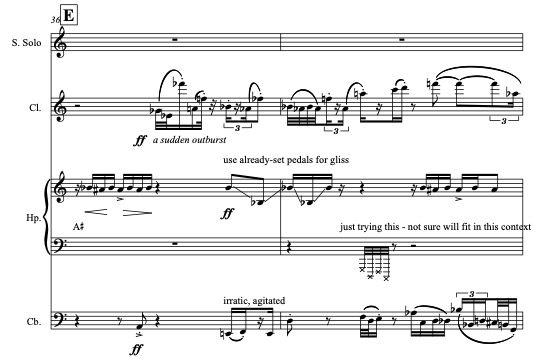

In the draft that I sent to The Hermes Experiment leading up to the workshop, it occurred to me that I had only written for Bb clarinet. So with the approval of clarinettist Oliver Pashley, I brought an additional sketch featuring bass clarinet in the third song for him to test in the workshop:

I really liked the effect of this and I think I will opt to use the bass clarinet here in this song. But then, this creates a new problem, namely, I think I need to identify at least one other place in the cycle to justify the use of this resource (side-note: I am haunted by a time as a university student when I included a bass drum in an orchestral piece and only called upon the percussionist to strike it once. The effort to set up the bass drum was not commensurate with my deployment of it in the piece). As mentioned above, it’s possible that the bass clarinet might be purposefully deployed in song 1, so this will inform my decision-making as I go forward.

Notation

I’m very interested in exploring different ways to notate ideas with a view to finding the way that will make optimal sense to a performer and ultimately to convey my idea most clearly. In the third song I have used a couple of arpeggiated flourishes in the clarinet, and following discussion with Oli, we decided it would be more effective to notate the rhythm more freely as a group of 11 demisemiquavers in the time of a beat, perhaps with a feathered beam to indicate a slight accelerando effect.

Writing for double bass

The text at the start of song 5 begins with mention of the double bass: “the double bass of rollers breaking”. I was very conscious of aiming to make a feature of the double bass in this song particularly. However, I think that what I tested out here didn’t convey the effect/impact that I was looking to create. In the next example you can see that the performer (Marianne Schofield) is required to stretch right up to her highest register. She indicated that while playable, if I’m wanting to evoke a more recognisable sense of “double bass”, then it would be preferable to drop the line by an octave – still in a “singing” register, but less ungainly to produce and more sonically identifiable as a double bass.

We made some other refinements to details of the double bass part, for example, in song 4, bar 55 I included some intricate pizzicato material. Marianne observed that the second and third beats would be more effective moved down an octave.

And in bar 37, beat 4, of the same song, I’d written a gesture that pushed the limits just a bit too much in terms of the clarity, definition and playability, so I will be streamlining this to a pair of semiquavers followed by a triplet semiquavers.

Writing for harp

Prior to the workshop I had already carried out a fair bit of revision to my harp part based on some feedback that Anne Denholm had emailed to me. Although I’ve written for the harp before in orchestral pieces and have a working knowledge of things to do with tuning, pedals and enharmonic spelling, there was still so much that I have learned from this experience of writing for the instrument in a chamber context. A key point of learning for me concerns the notation of gestures that feature repeated notes. I use repeated notes as a prominent feature in the first song. To maximise resonance, it is necessary to play the second note as an E# rather than re-plucking the same F string which will already be vibrating. So the opening gesture looks like this:

In an earlier draft of the harp part I had used a variety of note patterns going in alternating directions, eg. going down in the middle of a group of 3 triplet semiquavers (see example 13 a below). Anne explained that while this is playable, I might consider using more groups where each of the triplets goes in the same direction. By doing this, I would take into better account the way that harpists prepare notes in the direction of travel. If there is a lot of oscillation in direction, it makes the part much more cumbersome. See example 13b for the revised version:

And finally, Anne recommended that I indicate my intentions for string resonance in each song. For example, I might include a note at the start of each song that strings should be allowed to vibrate (l.v.), and if not, to indicate damping.